On March 2, 2022, Roman Abramovich released a statement outlining his intentions to sell Chelsea FC after almost 19 years of ownership. The club, winner of the FIFA Club World Cup (CWC) just a few weeks ago, enjoyed their biggest successes under the Russian tycoon, winning five Premier League and two UEFA Champions League (UCL) titles amongst many others.

According to media reports, the bids for Chelsea – managed by Raine, a merchant bank focused on advising and investing in the technology, media and telecom sectors – are approaching the GBP 3bn (EUR 3.6bn, USD 4bn) mark. This figure would top the highest fee ever paid for a sports organization, (the USD 3.35 billion Joseph Tsai paid for the acquisition of the NBA’s Brooklyn Nets and their home arena in 2019) and would also be over four times more than the highest price paid for a football club, namely the GBP 790m the Glazer family used to purchase Manchester United FC’s shares between 2003 and 2005. In terms of recent transactions, the predicted price would also be ten times as much as the latest takeover of Newcastle United FC in the same league.

Four consortiums are in the final shortlist at the time of writing, all backed by significant American investment with established interests in sports:

- A group led by NBA Boston Celtics’ co-owner Stephen Pagliuca, co-chairman of Bain Capital, who also purchased a 55 percent stake in Italian side Atalanta BC last month;

- A consortium led by MLB Los Angeles Dodgers’ owner Todd Boehly, backed by Clearlake Capital;

- MLB Chicago Cubs’ owners, the Ricketts family;

- Crystal Palace FC’s co-owners David Blitzer and Josh Harris, together with English businessman Sir Martin Broughton.

The question on all stakeholders’ minds is: What is Chelsea’s fair value? A question we are thrilled to help answer.

Football Benchmark have undertaken the estimation of the Enterprise Value (EV) of the most prominent football clubs in Europe since 2016. The table below summarizes some key financial information about Chelsea FC and three selected comparable clubs from their most successful financial years in this period.

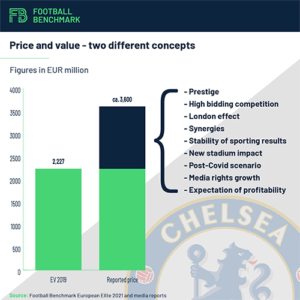

According to our expert opinion, there are football clubs whose fair market value on January 1, 2020, has come close to a EUR 3.6bn price tag. Real Madrid came closest in 2020, when their EV midpoint reached EUR 3.5bn and their top range reached EUR 3.6bn. Manchester United FC have also managed the eclipse the EUR 3bn mark, while FC Bayern München were just shy of reaching this threshold. However, Chelsea FC appear to be lagging, as their highest EV ever recorded is significantly below, at EUR 2.2bn, with a top range of EUR 2.3bn. It is also interesting to note that, although marginally, Chelsea’s best performance was from 2019 and not from the last pandemic-free season (2020) – unlike the rest of the peer group – signaling that their EV trend deviated from the upward trajectory they were on before, due to failed qualification to the UCL and worsened player trading activities. In our latest, 2021 valuation also examining the impact of the COVID crisis, EV values have fallen significantly for all clubs. The stock market valuation shows a similar trend, as an examination of Manchester United FC’s Enterprise Value on the New York Stock Exchange demonstrates: the club’s valuation was close to EUR 3.5bn in early 2020 pre-pandemic, but since then it has fallen considerably, as on the first trading day of 2022 their EV stood at EUR 2.7bn (-23%).

Another aspect that separates the Blues from their peers is their net results over the past ten years. They are the only club in this shortlist of elite clubs to have registered an aggregate net loss, while the other clubs successfully generated profits for their owners. The major reason behind this stark difference is the way Abramovich ran the club, chasing on-pitch successes to the detriment of financial performance. In fact, the club still owed EUR 1.6bn to him at the closing date of the 2020/21 financial year, but Abramovich decided against calling in the loans. (See a previous analysis on Chelsea’s financial evolution in the Abramovich era here.)

Top clubs’ valuations above stood at four to five times their yearly total operating revenues at the peak of the football industry’s growth. Comparing the reported price tag of EUR 3.6bn to Chelsea’s highest annual total operating revenues they ever recorded – EUR 513m in the 2018/19 season – the EV to total operating revenue multiple stands at around seven, notably higher than what past data shows.

Price and value – two different concepts. What are the possible explanations for such a vast gap between estimated value and reported acquisition price?

The prestige of a club like Chelsea FC, the scarcity of clubs at such stature for sale, combined with the ego-driven desires of investors in wanting to own such a trophy asset are perhaps the biggest drivers for such an expensive quote, as the opportunity to purchase the reigning CWC champions comes around once in a lifetime. The Blues are under tremendous sell-side pressure, which under normal circumstances would drive the valuation down, but the abundancy of the potential suitors in tandem with the urgency of the bidding process inverses this effect.

Further reason for a premium investment is Chelsea FC’s brand, that can be monetized globally and could create specific synergies to one or more of the interested bidders. Chelsea FC are also uniquely positioned because their local market is London, one of the cultural and economic capitals of the world; not only does this enhance the club’s reputation massively, but it also brings many competitive advantages in all facets of the club’s operations, be it negotiating with potential players and staff or striking up better commercial deals.

There are also advantages on the sporting side for buying an already established UCL club. In the financial fair play era, climbing up from the middle or lower tier of clubs has become a harder venture, one that many have attempted without success in the past decade. Furthermore, downward movements from the so called Big 6 in the Premier League is much stickier; thus, investing immediately at the top significantly reduces the uncertainty of sporting results.

While Chelsea FC are already one of the biggest clubs in the world, it can be argued that they still haven’t reached their full potential due to their current stadium limitations, meaning interesting upscale potential has remained untapped. The club currently own only the ninth biggest stadium in the Premier League, and the fourth largest in London. According to media reports, Abramovich stipulated in the club’s sale that the new owners need to commit to significant stadium infrastructure upgrades. An industry brochure released by the club outlines that increasing the stadium capacity from 42,000 to 62,500 could allow new owners to boost annual matchday revenues from GBP 70m to GBP 200m. Furthermore, a state-of-the-art venue also bring additional income through stadium naming rights deals, considered to be the third most lucrative source of revenue for clubs in the field of commercials, behind shirt sponsorships and kit suppliers. Clearly, there is a lot of unexploited potential for the club in this regard, however, to realize this promising future, significant monetary commitments must be made. Abramovich’s previous plans of stadium redevelopments were reported to cost several hundred millions of euros.

Finally, expectation of growth returning to normal following the difficult pandemic period, as well as the further growth of broadcasting rights at English Premier League (EPL) and UEFA level, might be another crucial factor in explaining the difference between price and value. While EPL domestic rights seem to have plateaued, international broadcasting rights are still on the rise. For the 2022 to 2025 rights cycle, international deals are reported to be worth GBP 5.3bn, up 30% and overtaking domestic deals (GBP 5.1bn) for the first time. UEFA TV rights are soaring – the current cycle is worth EUR 9.1bn over three years, up 11% on the previous three-year period.

In conclusion, while on one hand, looking at the financial performance and expected cash flows, it is very hard to justify such reported price and return on investment for an investor, on the other hand, as explained above, externalities and market dynamics – possibly difficult to specifically quantify at this stage and unique to each investor – may drive up the price. This is particularly true in a highly competitive bidding process, especially if further fueled by big egos. Don’t forget: what you pay for a product, is not necessarily its fair market value!